Oleg Yarosh

State, Denominationalism and Public Islam in Ukraine

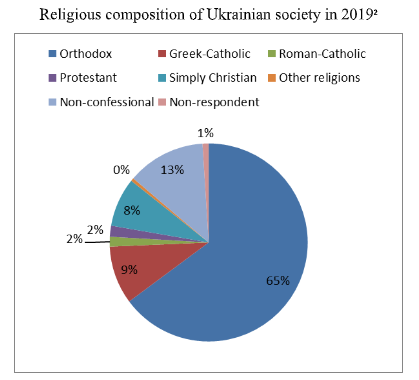

After the collapse of the Soviet Union when freedom of religion was enacted, the religious situation in Ukraine has developed in a different way, compared to the neighboring countries. Today Ukraine is a multi-faith society, where religion plays an important role in the social interactions and identity construction. According to the survey conducted by the Ukrainian Centre for Economic and Political Studies named after Olexander Razumkov in 2019, the number of those who recognize themselves believers is currently 66%, while the number of those who varies between faith and unbelief is 12,2%, the number of unbelievers is 5,4%, the number of convinced atheists is 4%, the number of those indifferent to matters of faith 6,5%, the number of those who did not decide on matters of faith is 5,9%.

Jose Casanova continuously claims that the situation in Ukraine is characterized by multi-religious denominationalism similar to that of the USA. To quote Casanova,

“In Ukraine, as none of the churches was able to become a national church because the new state decided to remain neutral and not to stand on the side of the Moscow Patriarchate, the Kyiv Patriarchate, or the Greek Catholic Church. An open field of religious competition emerged here. And then pluralism began to develop. As the four largest churches became denominations, other religious minorities, sects, also became equal denominations. … Denomination means simply a name by which I call myself and by which others recognize me. There is no similar term in any European language. It is translated either by the word confession, which means mandatory religion, imposed from above because a sect that denotes religious minorities, while a denomination is neither a church nor a sect. This term destroys the binary category of church and sect, and they all become equal denominations. And this is called denominationalism, a system in which all religions have equal rights and compete with each other. This is a unique model that has evolved in the United States for historical reasons. And Ukraine is the only country in Europe that has a similar church structure and the same historical causes” .

This is for the most part correct, but at least until January 2019, when Orthodox Church of Ukraine was officially recognized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate, Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Moscow Patriarchate was predominant in Ukraine, except the western part, and in some way prioritized by the State. Usually, services on official religious holidays organized by the Church were attended by the Ukrainian statesmen.

The Constitution of Ukraine adopted in 1996 provides for freedom of religion and worship. This right could be restricted only in the interests of protecting public order, the health and morality of the population, or protecting the rights and freedoms of other persons. The constitution provides for the separation of church and state and specifies that no religion shall be recognized by the state as mandatory.

According to the Law of Ukraine on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organizations, passed in April 1991, before Ukraine become independent, the objective of religious policy is to restore full-fledged dialogue between representatives of various social, ethnic, cultural, and religious groups to foster the creation of a tolerant society and provide for freedom of conscience and worship.

The law provides for a special state authority for religious affairs designed to assure implementation of state policy in respect of religion and church. Initially these responsibilities were assumed to the State Committee of Ukraine for Religions and Nationalities as an independent governmental institution, later it was downgraded to a department of the Ministry of Justice of Ukraine and then moved to a department of the Ministry of Culture. In 2019 it was transformed into the State Service of Ukraine for Ethnopolitics and Freedom of Conscience as a central executive body coordinated through the Minister of Culture and Information Politics of Ukraine, that deals with the implementation of state policy in the field of religion and the protection of the national minorities’ rights.

According to the law, religious institutions have to register both as religious organizations and nonprofits organization to get a legal entity status. They must register either with the State Service or with regional government authorities. Without legal entity status, religious groups are not able to have property, conduct banking activities, or publish materials. Most cases of delay of the registration are reported to the regional government authorities.

Since 1991 various amendments to the law have been adopted. In particular, in the sphere of religious education, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine in 2015 passed the law that granted religious organizations whose charters were registered to establish educational institutions.

Muslims represent one of the religious minorities in Ukraine. Government agencies and independent think tanks estimate the Muslim population at 500,000. Some Muslim leaders put the number at two million. According to government figures, 300,000 of these are Crimean Tatars.

The ethnic history of Islam in Ukraine goes back to the Crimean Tatar and Lipka Tatar population in the early modern period. The later development of Muslim minorities in Ukraine is connected to the population mobility in the days of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union.

In general, policies towards religious minorities in Ukraine including Muslims generally remain non-restrictive and comply with the freedom of religion principles.

Last year President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy on the occasion of Eid Al-Adha on July 30, 2020 congratulated Muslims of Ukraine and the world on the beginning of the Eid Al-Adha and signed a decree, instructing the Cabinet of Ministers to consider granting official status to certain religious holidays, such as Eid Al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha, Pesach, Rosh Hashanah, Hanukkah, Christmas and Easter of Western Christians. The law will introduce a regulation, according to which the employer is recommended to provide a day off to an employee who celebrates one of these holidays in accordance with the affiliation to a particular religious denomination. The government should discuss this issue with the All-Ukrainian Council of Churches, religious organizations and the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, and then submit a draft law to the Verkhovna Rada.

The main Islamic institutions in Ukraine are:

- Religious Administration of Muslims of Ukraine, established in 1992. It is connected to the Association of Islamic Charitable Projects (Jam'iyyat al-mashari' al-khayriyya al-Islamiyya) known as Al-Ahbash or Habashiyya is a transnational network of Muslim Sufi-oriented organization.

- Religious Administration of Muslims of Ukraine “Ummah”, established in 2008. It promotes a culturally disconnected version of Islam for Ukraine and Ukrainians as a part of the European socio-cultural space, and “civic Islam” active in the public sphere.

- Religious Administration of the Muslims of Crimea, established in 1991. It currently operates under the jurisdiction of the Russian Federation.

- Religious Administration of Muslims of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, established in 2017. The organization represents “pro-Ukrainian” Crimean Tatars, mostly refugees from Crimea.

- Religious Center of Muslims of Ukraine in Donetsk, established in 1994.

- The Association of Ukrainian Muslims, established in 2012. It represents Salafi Muslims, a group that has increased after the influx of internally displaced people from Crimea and also includes Ukrainian converts.

Along with religious organizations we should mention the All-Ukrainian Association of Social Organizations “Alraid” that runs several Islamic Cultural Centers across Ukraine.

Jose Casanova introduces the concept of “public religion”, which I find quite heuristically valuable, despite of criticism by Talal Asad, namely, a religion that is already public or seeks to acquire a public character, function, or meaning, and identifies three levels at which this publicity is realized, and conceptualize the appropriate types of public religion:

- at the state level – officially recognized state churches;

- at the political level – religions that perform a mobilizing function to participate in the political struggle;

- at the level of civil society – religions that go to a public forum – i.e. to the undifferentiated public sphere of civil society – to participate in open public discussions on res publica: public debates, public affairs, public policy, and the common good in general.

I would argue that “Islam of minorities” could be regarded as a third type of public religion, that is at the level of civil society.

Reinhard Schulze puts forward the idea of “Islamic public sphere” - communication infrastructure, formed in the late nineteenth century through the efforts of Muslim reformers and the emergence of a new intellectual elite, which develops in the structural transformations of the Muslim world from the 60-70s of the twentieth century to the present. Abdulqader Tayob argues that that the concept of the public sphere is useful for understanding important processes in modern Muslim societies. On the one hand, the public sphere becomes a space for the formation of new identities, and on the other hand, its development contributes to democratization in Muslim countries. I think that we could extend this notion to the Muslim minority-countries, in particular Ukraine.

Muslim organizations in Ukraine are becoming increasingly active in the public sphere. This is especially true of the Religious Administration of Muslims of Ukraine “Umma” and “Alraid”, which are developing a “civic”, socio-culturally adapted Islam, coordinating its efforts with other religious minorities. In 2016, the Religious Administration of Muslims of Ukraine “Umma” and several religious organizations representing religious minorities formed a new collective representative body, the All-Ukrainian Council of Religious Associations, separate from the All-Ukrainian Council of Churches and Religious Organizations, which includes another influential Muslim organization, the Religious Administration of Muslims of Ukraine.

The Religious Administration of Muslims of Ukraine “Umma” supports the volunteer movement and promotes the establishment of a Muslim military chaplaincy in Ukraine. It has played a leading role in the adoption by several Ukrainian Islamic organizations of the Charter of Muslims of Ukraine, based on the Charter of Muslims of Europe (2000), in 2016 and the Social Concept of Muslims of Ukraine in 2017. The two above-mentioned documents outline the principles governing the existence of Muslim communities in Ukrainian society and the state.

Muslim organizations in Ukraine are actively involved in charity, helping socially disadvantaged people, people with disabilities, and prisoners. Also, the Religious Administration of Muslims of Ukraine, the Religious Administration of Muslims of Ukraine “Umma”, “Alraid” and other Muslim organizations implement educational and information projects.

Finally, I would like to outline some scenarios concerning the interaction of the Islamic tradition (T. Asad) with the public sphere of Muslim-minority countries, because Islam is a relatively new factor there and currently, they are all present.

The first scenario is in line with integration strategies, proposed by the Western political elites and proponents of modernization among the Muslim leaders. It is based on a rethinking of the Islamic tradition as the basis of the collective identity of Western Muslims, which implies maximum adaptation to Western socio-cultural norms and values, but with the preservation of the essential Islamic religious norms and practices. The positive aspect of this strategy is the opportunity to quickly and successfully integrate into Western society and the public sphere. However, such a strategy does not exclude the threat of erosion of religious identity, and does not take into account the significant number of Muslims who do not accept the idea of modernization and reconsideration of the Muslim tradition.

Another approach is creating alternative public spaces, i.e., Muslim counter-publicity in the West. In my opinion, it will significantly complicate communication and dialogue with other public actors, deepen the “ghettoization” of Muslim communities and social distance. Given that Muslims in the West belong to different schools, such an approach is unlikely to strengthen social solidarity among Muslims, and the Islamic public sphere will become a space of controversy and conflict rather than dialogue. This will create obstacles to the social integration and mobility of Muslims, who at the end will have to give up elements of identity that they themselves and their environment consider important for the sake of successful self-realization in the Western society.

The most productive, in my opinion, is the approach that is based on building of a common inclusive space of communication and dialogue, united around the idea of common good, where Muslims are recognized as bearers of a separate identity with their own rights and needs. This does not preclude the development of Islamic social institutions and publicity participating in the dialogue within the society, and will help avoiding conflicts with other societal groups.