Any fortuity is a sword or reward.

Eastern proverb

On June 27 (July 8), 1709, several kilometers from Poltava, the battle took place, which changed the history of all Eastern Europe for a long time and, above all, the history of Ukraine. The allied Swedish-Ukrainian army was defeated by the troops of the Russian Tsar Peter I, ending all attempts to create an independent Ukrainian state.

The defeated troops of Swedish King Charles XII and Ukrainian hetman Ivan Mazepa were forced to leave the Poltava battlefield in a hurry. At Mazepa’s suggestion, they decided to retreat to the Ottoman Empire territory. Zaporozhian Cossacks were guides in the Dnipro steppes. The only place, where the Swedes and Ukrainians could cross the Dnipro was Perevolochna settlement. That’s the place the defeated army began to retreat to.

The Swedish camp was depressed. The participant of the battle, K. de Tourville, wrote: "I was totally frustrated. I was feeling this left-out for several hours, so I could not even remember, who was the winner, or who had been defeated. "During the Battle of Poltava, the Swedes suffered heavy losses, but in general, they stayed combat-worthy and were still quite numerous.

Moving towards the Dnipro was well-organized. There was no panic. At least 25 thousand Swedish soldiers, officers, and several thousand Ukrainian Cossacks approached Perevolochna. It was a well-known crossing point. But before the Battle of Poltava, Russian troops had burned Perevolochna along with the boats. An attempt to build a bridge was failed, because there was little building timber for this purpose. The Swedes tried to use the old church, disassembled to logs, as a waterborne platform, but they also failed - badly tied logs were washed downstream. Afterall, the soldiers of Charles XII found several small ferries, on which they transported the king and his retinue. Mazepa, along with a group of close friends, crossed the river by fishing boats.

Russian troops under Menshikov command were literally following upon the Allied armies heels. By the time Tsar’s troops approached, only a small part of the Swedish army had crossed the Dnipro. Menshikov blocked the Swedes, commanded by General Levengaupt. Trapped in a difficult situation, they capitulated. At least 16 thousand Swedes were captured by Russians. Along with them, several hundred Ukrainian Cossacks were also taken captives and later executed. Charles XII and Ivan Mazepa were able to avoid captivity, continuing their way to the Turkish possessions.

Levengaupt’s capitulation surprised all, Peter I and even Charles XII himself. Later, the Swedish king wrote: “Levengaupt acted contrary to orders and military duty, in the most shameful way, and caused an irreparable loss that could be less even if he had taken the bold risk... I do not think he did like this due to the intentional maliciousness or personal faintness. But in war, it's not an excuse, and he, seemed completely lost his mind and shrank to act as a general in a difficult moment."

Having lost their supply train, including food, the remnants of the army were doomed to hunger and misery. De Tourville wrote: “Unknown parts of the path, hunger, thirst, heat during the day, and cold at night certainly foreshadowed the death to that unfortunate detachment. There were no villages, houses, huts, trees, or fruit on the road. We could see neither road and path, nor people’s traces. ” The Swedes and Ukrainians could buy enough food from the Turks only on the way to the Ottoman possessions near the crossing of the Southern Bug river.

Retreating into the territory of the Ottoman Empire, Charles XII and Mazepa thought the Turks and the Crimean Tatars would not miss the opportunity to attack Russia that makes tremendous efforts to defeat Sweden. These thoughts were reasonable. Even before the battle of Poltava, the Crimean khan Devlet II Giray was ready to help Charles XII and Hetman Mazepa, but Istanbul’s restrained position forced him to abandon this risky step.

The remains of the Swedish army passed by Ochakov, and Khadzhibey fortress ruins, and stopped only in Bendery. The Swedish king, while being on the road, sent his ambassador Neugebauer to Istanbul to conclude an alliance against Russia. Sultan Ahmed III ordered seraskir Bender Yusuf-pasha to provide Charles XII with all possible hospitality. The Turks supplied the Swedes and the Ukrainian Cossacks with food and allowed them to set up a camp near the city walls.

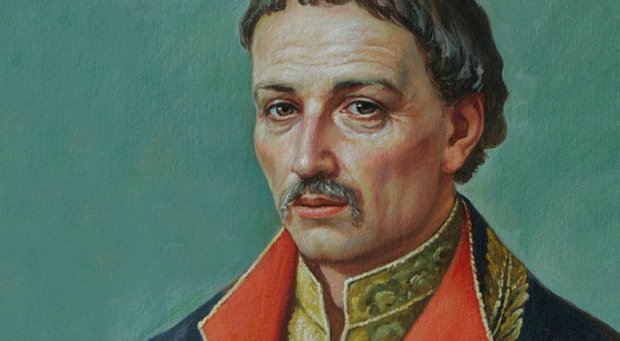

On August 22, 1709, Hetman Ivan Mazepa died in Bendery. Cossacks elected Pylyp Orlyk as a new hetman, who was as reliable ally for the Swedes and Turks as Mazepa was. Meanwhile, Peter I repeatedly demanded the extradition of the Swedish king through his ambassador in Istanbul, threatening to start military action against the Ottoman Empire. In the Turkish capital, the pro-Russia party was prevailing for a little while, but the sultan had quickly enough of the tsar’s threats, and decided not only to save Charles XII, but to be the first who declared a war against Russians.

On November 20, 1710, the beginning of hostilities against Russia was announced, and already in February, Pylyp Orlyk together with the Crimean Tatars made a raid on Ukraine. For the first time since Hetman Doroshenko P., the Ukrainian Cossacks acted as allies of the Ottoman Empire and the Crimean Khanate. And although the raid had failed, it showed Peter I Ukraine’s insecurity. The Russian Tsar started to prepare a great campaign to capture the Danube territories.

Heaving learnt about Peter I offensive preparations, the Ottoman Empire’s vassal, the ruler of Moldavia, Dimitrie Cantemir, announced his adopting the Russian citizenship. Delighted by the prospect of getting support from the Moldovans, Peter moved his army to the Prut banks. But, it turned out that Cantemir himself needed a support. The food supplying of the troops was very poorly organized, and the local population barely wanted to share their own food reserves with Peter’s soldiers.

The Ottoman army, the Crimean Tatars’ army, led by Khan Devlet II Giray, along with Zaporizhzhya Cossacks’ detachment moved towards the Russian troops. The Turks had a lot of artillery, gunpowder supplies and enough food. Russian troops were surrounded and pressed to the bank of the river Prut. Their state was hopeless, and only due to the Grand Vizier Baltaji Mehmed Pasha’s betrayal, who agreed to sign a peace treaty, Peter I and his army managed to avoid defeat and captivity.

The Russian tsar was ready for serious concessions, but the peace conditions, negotiated with the Grand Vizier, were even softer. A significant amount of money that was promised to Mehmed Pasha played its role. However, he did not receive the promised money. A few months after the end of the war, the grand vizier was unseated and then executed.

Charles XII returned to Sweden to continue the war against Russia and its allies. He died from a stray bullet during the fortress siege in Norway. For the rest of his life, Pylyp Orlyk was making efforts to create an anti-Russian coalition of European countries. He never saw Ukraine again. Sultan Ahmed III waged wars in Europe and Asia with varying success, but he was overthrown by the insurgent people. Long before the Prut campaign, the courageous and brave Khan Devlet II Giray predicted the danger of the Russia’s rise. But the Sultan did not appreciate enough his faithful and reliable ally. Soon after the Prut War, he removed Devlet II Giray from the Khan's throne, sending him into exile.

Oleksandr Stepanchenko