Ukrainians have long struggled with fake news from Russia, but last week, they discovered something even more insidious: a fake journalist.

The man was tall and dapper. He wore a dark suit and spoke with a French accent. When he met politicians in Kiev, he introduced himself as Alex Werner, a reporter with the French newspaper Le Monde.

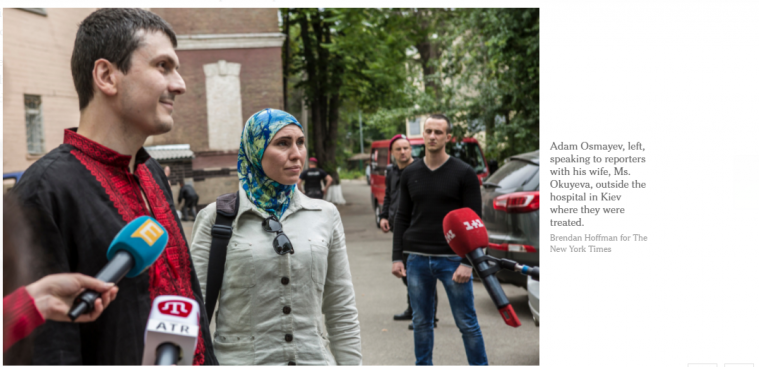

“He was elegant, calm and confident,” recalled Amina Okuyeva, who is a minor celebrity in Ukraine because she served with her husband as a volunteer soldier in the war against separatists in the eastern part of the country. Mr. Werner had interviewed her several times.

It was midway through one of those purported interviews, in a terrifying flash of gunpowder, that Mr. Werner’s true identity came to light: He was, in fact, a Chechen assassin, the Ukrainian authorities now say.

Under the guise of a journalist, the assassin, Artur Denisultanov-Kurmakayev, tried to murder Ms. Okuyeva and her husband, Adam Osmayev, Ukraine’s Interior Ministry said.

The plot went awry because Ms. Okuyeva was also armed, and the details of the attack and its aftermath are now shedding light on Kiev’s role as a testing ground for what Ukrainian officials say are hybrid war activities by Russia, including assassinations.

The attack was the third high-profile killing or attempted killing in Kiev that the Ukranian authorities have attributed to the Russian security services, but the first in which the accused killer impersonated a journalist.

In a statement published June 3, Le Monde said it “wants to stress that none of its journalists are in Ukraine at the moment and that its staff does not include an Alex Werner. Le Monde firmly condemns any impersonation of its journalists or of its title, for whatever purpose.”

In 2006, the Russian government legalized targeted killings abroad of people posing terrorist threats, resuming a Soviet-era practice. But the Kremlin has never acknowledged using the authority granted under the law and has vehemently denied specific accusations, including those in Ukraine.

As “Mr. Werner,” Mr. Denisultanov-Kurmakayev had lived for more than a year in Kiev, mingling with politicians and anti-Russian activists before the shooting on June 1.

Artur Denisultanov-Kurmakayev posed as a reporter from the French newspaper Le Monde but was in fact a Chechen assassin, according to the Ukrainian authorities.

The cover was good but not flawless, Ms. Okuyeva said in an interview, her first with a foreign news organization since the attempted murder. She was accompanied by two bodyguards who were on high alert throughout the interview.

One indication that Mr. Denisultanov-Kurmakayev was not who he said he was: He always carried a notebook but never bothered to write in it, Ms. Okuyeva said. He wore an expensive-looking suit, also a hint that something may have been amiss.

There was nothing unusual in the request for an interview, however. “The press often asked for interviews,” Ms. Okuyeva said. “The media loves to write about us.”

Ms. Okuyeva and Mr. Osmayev, both ethnic Chechens, are well known in Ukraine. In 2012, the Russian government accused Mr. Osmayev of plotting to kill Vladimir V. Putin, who was then the prime minister. Mr. Osmayev was arrested in Ukraine, but his extradition to Russia was blocked by the European Court of Human Rights.

After the Ukrainian revolution in 2014, he was released, and he and his wife joined a unit of ethnic Chechens fighting in the war in the east, the Dzhokhar Dudayev battalion. Mr. Osmayev has been its commander since 2015. Ms. Okuyeva served as a sniper, wearing a camouflaged head scarf at the front.

Gaining fame as enemies of Russia carried risks. The couple knew they were targets. “Putin is personally interested in getting rid of us,” Ms. Okuyeva said.

The putative Mr. Werner met three times with the couple in Kiev coffee shops from May 20 until June 1, explaining that he planned an in-depth article.

Before the fourth meeting, Ms. Okuyeva said, he asked the couple to pick him up in their car and drive to the French Embassy, and he also said he had a gift from his bosses at Le Monde.

“There were a lot of small, strange things, and my intuition told me not to meet with him,” Ms. Okuyeva said, but she ignored the misgivings.

As they drove, Mr. Denisultanov-Kurmakayev asked the pair to stop the car for an interview and to sit in the back to receive the gift, which he carried in a festive red cardboard box.

As the couple sat in the back seat of the car, Mr. Denisultanov-Kurmakayev said, “‘Now, here is your gift,’” Ms. Okuyeva said. He opened the box, pulled out a gun and opened fire on Mr. Osmayev.

A shot hit Mr. Osmayev on the right side of his chest. But he was not immediately incapacitated and struggled with the shooter for control of the gun. Ms. Okuyeva, however, long fearful of assassination attempts, was carrying a pistol under her coat, as well as a tube of the blood-clotting agent Celox in her purse. She shot Mr. Denisultanov-Kurmakayev four times as he and her husband fought. Both were gravely wounded but survived.

“I will always be thankful,” Mr. Osmayev said in an interview of his wife’s quick draw. “Because of her reaction, we are both alive today.”

The survival of the assassin could elevate the importance of the case, should investigators obtain his cooperation.

In March, a former Russian lawmaker who fled to Ukraine, Denis N. Voronenkov, was gunned down on a sidewalk outside the Premier Palace hotel in Kiev. Mr. Voronenkov’s bodyguard shot and killed the attacker. Last year, a car bomb killed a journalist, Pavel Sheremet, on a central street of the capital, and no arrests were made.

After the attack on Mr. Osmayev and Ms. Okuyeva, Ukraine’s Interior Ministry and lawmakers blamed the Russian intelligence services. Ukraine’s SBU intelligence agency, however, has said there is insufficient evidence to determine whether the killer pretending to be a journalist was a Russian agent, but it has not ruled out that possibility.

“For the world community, what is important is we have proof Russia is committing terrorist acts in other countries,” said Anton Gerashenko, a lawmaker. “His tongue may loosen to say who sent him here and why,” he said of Mr. Denisultanov-Kurmakayev.

While it remains unclear whose bidding Mr. Denisultanov-Kurmakayev may have been doing, it was not the first time his name had arisen in similar circumstances.

In the 1990s, Mr. Denisultanov-Kurmakayev was all but openly associated with a Chechen organized crime group operating in St. Petersburg, and he once appeared on Russian TV to speak as a representative of the organization.

In 2008, the authorities in Austria questioned Mr. Denisultanov-Kurmakayev about his contacts with a Chechen asylum seeker and whistle-blower, Umar Israilov, who had testified to the European Court of Human Rights against Ramzan A. Kadyrov, the Chechen leader. Mr. Israilov said Mr. Denisultanov-Kurmakayev was an envoy of Mr. Kadyrov sent to Austria to threaten his life.

Mr. Denisultanov-Kurmakayev said the Chechen leader had sent him to Vienna to persuade Mr. Israilov to return to Chechnya and, failing that, to murder him. He said that Mr. Kadyrov kept a list of 300 enemies to be killed.

Mr. Denisultanov-Kurmakayev said he had declined to carry out the assassination and instead turned to the Austrian police for protection against retribution for failing to fulfill the order. Two months later, Mr. Israilov was shot and killed by unknown gunmen on a Vienna street.

Mr. Denisultanov-Kurmakayev said at the time, “I do not want to break any laws, and I am not a murderer.”

Source: The New York Times