History of Islam in Ukraine is closely interrelated with Ukrainian independence. Before the late 1980s no single community officially existed in this part of the USSR. However, in 2014 around 700 Islamic communities were registered, including those on the Crimean peninsula. Since 1991, Muslims have become a significant and active part of the Ukrainian population, mostly in Kyiv, Crimea and some urban regions of Eastern Ukraine. Due to the ongoing political crisis and military conflict in the area, the Muslim part of Ukrainian society experienced various problems. Furthermore, this resulted in the appearance of new phenomena in the history of Ukrainian Muslim communities: that is, internal refugees, ethnic and religious persecutions as well as the rise of new Muslim organisations based on political loyalty. Moreover, after the Russian annexation of Crimea, local Muslims (which constitute more than half of the total Muslim population in Ukraine) entered a completely new legal and political reality. The same is true for Muslims of Eastern Ukraine (especially, for the areas around Donetsk and Luhansk), who, as well as other segments of the local population, continue to suffer from the protracted military conflict.

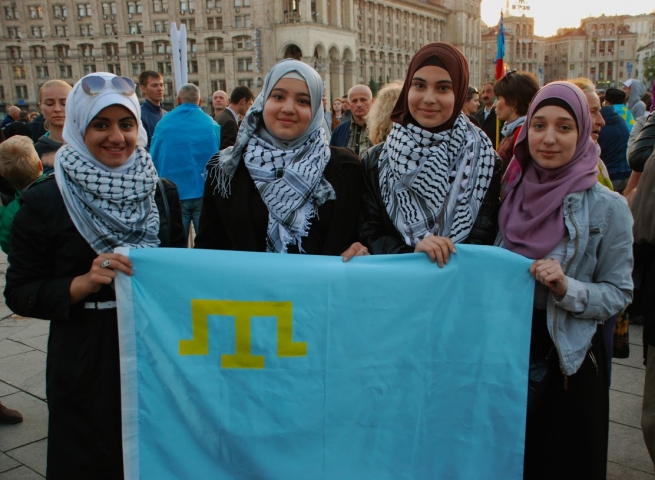

In contrast to past decades, it is even more difficult to speak about Islam in Ukraine as a single entity; there are already three regions with different political situations – Crimea, the military conflict zone of Donbass in the Eastern part of Ukraine, and the rest of the country. Facing this challenge, Muslim communities reacted differently rather than adopting a common position: some of them do not cease to propagate neutrality in the conflict while others have joined the pro-Ukrainian part of society (while also participating in the Ukrainian “Anti-Terrorism Operation”) and, finally, some groups support Russian political positions. As a result, one can observe not only a doctrinal clash between various traditions of Islam but also differences coming from divergent political loyalties and their international contexts. Beyond that, however, it is possible to observe new points of connection between Muslims and other religious communities in Ukraine, which have started campaigns to promote national reconciliation and peaceful dialogue in society.

Nevertheless, topics related to Islam and Muslims started to appear in press and media even more frequently than before; some Muslim leaders (especially those supporting the Ukrainian government) are welcomed in interreligious meetings, public events as well as TV-shows and other forms of public discussions of the current situation in Ukraine. In Crimea, where the Russian authority still continues to demonstrate its power in relation to Crimean Tatars, most Muslims organisations attempt to focus their projects around building new and restoring old mosques. Most “untraditional” Islamic groups (as they are usually described by the Russian media), however, such as Salafi communities, Hizb al-Tahrir al-Islami, etc. have already left Crimea for other parts of Ukraine. It is said that more than 20,000 Crimean Muslims (including not only religious, but also political activists) departed Crimea since the beginning of Russian control over Crimea in March of 2014. Thousands of them now live in Kyiv and Western Ukraine, mostly in the Western Lviv and Vinnytsia regions. According to official sources, there are around 500,000 “internally displaced persons” (as the Ukrainian government calls them) from Donetsk and Luhansk and at least few thousands among them are Muslims.

Already by the end of February 2014, when a group of militants captured the Crimean parliament, the opposition of Crimean Tatars to secessionist moves, and their boycott of the controversial and unrecognised referendum of 14 May 2014 to legitimise Crimean secession, became subjects of discussions in the media. Mustafa Dzemilev, a Ukrainian MP and former leader of the Mejlis of Crimean Tatars, was at the centre of attention. The same was true about Refat Chubarov, the current head of the Mejlis of Crimean Tatars. Both were labelled “extremists” by Russian authorities and banned from entering Crimea in July 2014. In the following months, the “Muslim issue” in public debates mostly covered the pressure of Russian authorities on the Crimean Tatars, the plight of Crimean refugees and police raids on Islamic religious institutions on Crimea (for example, search of the madrasa in Kolchugino on 24 June 2014). The reasons for these raids were not officially given.

The rights of Crimean Muslims was one of the main topics of some press conferences, held on the issue of religious freedom in Ukraine. One was organised by the Ukrinform agency on 25 November 2014 and gathered representatives of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Kyiv Patriarchate), the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church, members of Jewish and Protestant communities and the Mufti of the Dukhovne Upravlinnya Musulman Ukrainy “Ummah” (Spiritual Administration of Ukrainian Muslim “Ummah”, SAUM “Ummah”), Said Ismagilov. The speakers concluded that the rights of Muslims are violated in Crimea and in the Donbass area along with the rights of other religious groups. In general, attitudes towards Muslims in Ukrainian public opinion have been transformed since the beginning of the military conflict. In contrast to previous years when negative media portrayals of Muslims were dominant, such headlines were absent from the media in 2014. Moreover, many appreciative comments were made about four Muslim candidates running for seats in the Ukrainian Parliament during the last elections. In addition, the media covered the activities of a special Muslim police squad, called “Crimea”, which has participated in military campaigns since July 2014.

In 2014, Ukrainian Islamic communities intensified their contacts with foreign Islamic institutions. First of all, all Islamic religious leaders (usually called “muftis” in Ukraine) participated in some international events both in Ukraine and abroad. Ahmad Tamim, Mufti of the Dukhovne Upravlinnya Musulman Ukrainy (Spiritual Administration of Ukrainian Muslims, SAUM, headquartered in Kyiv), made two official visits to Egypt in January and March 2014. First, he visited the former Egyptian mufti ‘Ali Jumaa and the rector of Al-Azhar University; in March and participated in the international conference on “Takfiri Ideology” in Cairo. His visit received some attention in Egyptian press, as evident in his extensive interview given to the Al-Ahram newspaper. His usage of the title “Mufti of Ukraine” during this visit, however, caused a significant discussion among Ukrainian Muslims, since in Ukraine, as a constitutionally secular state with no state religion, muftis represent only particular organisations and are not state-appointed. However, in his later interview with the Al-Misr al-‘Arabi newspaper, Ahmad Tamim recognised the absence of the official title “Mufti of Ukraine”, while also defending the de facto use of this title, because he was elected mufti by a significant portion of Ukraine’s Muslims in 1992. Finally, he accused the Muslim Brotherhood (claiming that one of the Ukrainian Islamic Associations, Alraid was its “representative”) of spreading these accusations against him and, specifically, Yusuf al-Qaradawi, “of waging a war against him for years.” This example shows that internal conflicts among Ukrainian Muslims are partially repercussions of wider conflicts in the Muslim world, such as global tensions between pro-Sufi groups and contemporary Islamist movements.

Other Islamic communities were active internationally in 2014 as well. Said Ismagilov, Mufti of the Islamic organisation Ummah, visited Georgia in April 2014. Apart from his speech at the international conference on Islamic issues, Said Ismagilov signed an agreement of cooperation with the head of the Georgian Muslim Union, Zurab Tsickhiladze. Ummah also welcomed many foreign guests not only of Muslim but also of Christian background: for example, in October 2014, this Muslim organisation was visited by bishops of the Ukranian Greek Catholic Church from France and Canada. Another Islamic organisation, the All-Ukrainian Association of Islamic Organisations Alraid, which cooperates with Ummah very closely (in fact, Ummah appeared with the support of Alraid), continued its cooperation with global institutions; first of all, with the International Islamic Federation of Student Organisations (IIFSO). For instance, in June 2014 members of Alraid along with other Muslim activists from around 50 countries attended an international conference in Istanbul titled “A Future of the Islamic World and the Muslim Youth.” Since Alraid unites a significant number of the immigrants from Arab countries, it has already developed very strong links with the Islamic institutions from Middle Eastern countries (UAE, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Egypt). Moreover, Alraid runs an Arabic-language web-site Ukrpress, delivering first-hand information about current events in Ukraine to readers in the Arab world.

The political climate determined much of the international activities of Crimean Muslims. In March and April 2014, when the annexation of the peninsula just happened, the Dukhovne Upravlinnya Musulman Krymu (Spiritual Administration of Crimean Muslims, SACM) was visited by representatives of the Russian Islamic community. On 28 March 2014, Mufti Emirali Ablaev hosted a delegation from Moscow, consisting of the Chief of the Russian Council of Muftis, Ravil Ghainutdinov, Vice Chief Damir Muhetdinov, the imam of one of the Moscow mosques, Shamil Alautdinov, and some other notables. Russian Muslims declared their support for Crimean believers, promising to assist them in the solution of some critical issues “for the sake the peace and prosperity in Crimea.” Later, on 12 June 2014, SACM welcomed the Mufti of the Central Spiritual Administration of Russian Muslims, Talgat Tajuddin. His goal, as it may be seen from press-releases, was to establish close links between Crimean and Russian Muslims. He also made a reference to some common historical ground between both groups, mentioning the “Tavrian Mohammadan Spiritual Governorship” as the first Crimean Islamic institution in the Russian Empire as well as the “Orenburg Mohammadan Spiritual Governorship” (the oldest state-controlled Islamic organisation in Russia). Other Islamic institutions of Russia were interested in visiting Crimea as well. Sometimes these visits served not only religious but political purposes, in order to develop new links between Crimea and the pre-dominantly Muslim regions of Russia, like the republics of the Northern Caucasus. Many Islamic leaders and scholars from Russia visited Simferopol on 15 October 2014, while participating in a conference dedicated to the preservation of Islamic religious heritage in the area.

Among Islamic leaders from other countries, one of the few of them was the Mufti of Polish Religious Union, Tomasz Mickiewicz, who met Mufti Emirali Ablaev along the members of the Mejlis of Crimean Tatars. In contrast to the leaders of Russian Muslims, he abstained from any political declarations, talking mainly about his deep sympathies for the problems facing Crimean Muslims.

During 2014, none of the Islamic leaders from other parts of Ukraine were able to visit Crimea; it seems that preserving the connection between these communities may be a serious challenge for Ukrainian Muslims in the future. It must be noted also that many Crimean Muslims made their pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina this year based on the quota, issued by Saudi Arabia for Russian Muslims; the cost for the pilgrimage was reduced by the Russian side, probably to gain more loyalty among Crimean Muslims.

In some parts of Donbass regions, where pro-Russian militants proclaimed their unrecognised state of Novorossiya (consisting of “Donetsk People’s Republic” and “Luhansk People’s Republic”), some Muslim leaders joined the new state authorities. Rinat Aysin, a head of the Islamic organisation Ednannia (Unity) became “Counsellor in Religious Affairs of the Head of the Highest Council of the Donetsk People’s Republic.” In October 2014, he visited the Moscow Muftiate to establish some new links of cooperation between the Muslims of Moscow and Donetsk. In one of his interviews, Rinat Aysin talked mostly about humanitarian issues and not political ones. He represents, however, just a minority among Muslims of the Donbass region. Other international activities of Donbass Muslims were almost impossible to undertake due to the military conflict in the region.

International Islamic organisations have responded to the events in Crimea and Donbass quite reservedly. What seems to be significant in this context is Mustafa Dzemilev’s meeting with Iyad Madani, the Secretary General of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Madani informed Mustafa Dzemilev that there is the possibility for Ukraine to become an associate member of the OIC. Also on 3 May 2014, the European Muslim Union (EMU) organised special hearings on Islam in Ukraine (“Solidarity with an embattled minority”) in Berlin; Crimean Muslims were represented by Abduraman Egiz from the Mejlis of Crimean Tatarian people.

Notwithstanding the fact of the political and military crisis in Ukraine, many Muslim communities made their best efforts to continue their activities. First of all, in 2014, around 200 Ukrainian pilgrims visited Mecca and Medina for the hajj. SAUM continued its tradition to organise “diplomatic iftars” during the month of Ramadan, inviting state officials and ambassadors of foreign countries, mainly from the Middle East. SAUM also organised celebrations of the main Muslim festivals (including celebration of mawlid, the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday) in regional Muslim communities. Members of the Islamic University (founded by SAUM) participated in some Ukrainian book fairs with their publications. The head of SAUM, Mufti Ahmad Tamim, visited many public events in Ukraine and abroad.

Another Islamic institution with its centre in Kiev (SAUM Ummah) organised events to initiate cooperation between Ukrainian Muslims and scholars of Islamic Studies. Along with the Association Alraid, SAUM Ummah ran a summer school of Islamic Studies in August 2014. Mufti Said Ismagilov was among the co-organisers of the Fourth International Conference “Islam and Islamic Studies in Ukraine”, which was held by the Institute of Philosophy of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine on 19 November 2014. Besides traditional celebrations of Muslims holidays and other religious activities, SAUM Ummah and the Association Alraid published statements on current events in Ukraine, such as the presidential elections, the celebration of Ukrainian Independence Day etc. In some parts of Donbass, however, public activities after May 2014 have become extremely difficult because of the military conflict. As a result, Muslim communities there were more concerned with the issue of survival than with the usual schedule of religious activities.

In Crimea, the most prominent Islamic event was an international conference in October 2014, dedicated to the 700th anniversary of the construction of the Khan Uzbek Mosque in Solhat. The meeting was run by the SACM, the “Council of Ministers of Crimea” and some Islamic institutions from Russia. The conference gathered many Islamic leaders, officials, and scholars from Russia, Belarus, and Turkey, but no speakers from other parts of Ukraine were able to attend the conference.

A few recently constructed mosques were opened in 2014 in the cities of Simferopol, Novozhylovka and some other places. A new Islamic organisation, the Central Spiritual Administration of Crimean Muslims (“Tavrian Muftiate”), headed by Ruslan Saitvaliev, was established in 2014. This institution gained control of one of the main mosques of Yevpatoria (Juma-Jami). The Central Spiritual Administration of Crimean Muslims has a close links with the Central Muslim Religious Administration of Russia.

For more details, see the article: Mykhaylo Yakubovych. Ukraine, in: Yearbook of Muslims in Europe. Vol. 7. Ed. by. O. Scharbrodt. Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2016. PP. 592-607. Forthcoming report on the 2015 is going to be published in Vol. 8 of the same Yearbook.