Series profiles the Golden Age of Islamic culture and discovery, between the 9th and 12th centuries: a renaissance that preceded the Western one by some 300 years.

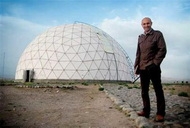

Jim Al-Khalilli begins Science and Islam, a three-part BBC series on TVO, gazing down from a balcony on a view of mosques and minarets. He's a scientist, who was born in Baghdad and whose family left Iraq when Saddam Hussein came to power; he's now a professor of physics at Surrey University. He sounds, and admits to being, thoroughly Westernized, but the series he presents is born of what he calls "a nagging feeling" that he needed to re-examine his roots and find a connection between them and his present existence. He "can no longer visit Baghdad because of recent events" but his quest takes him through Syria, Iran and North Africa. He's a model TV explorer, very winning and unaffected.

His subject is the Golden Age of Islamic culture and discovery, between the 9th and 12th centuries: a renaissance that preceded the Western one by some 300 years. We know, and probably take for granted, that we owe our system of numbering to it. Al-Khalilli asks us to consider just how revolutionary was this idea of using 10 numerical symbols. It was developed, he tells us, by Indian mathematicians in the 6th century AD; a century later the Arabs took it further by inventing the decimal point, thus making modern math possible: "like all great science it's blindingly obvious after it's been discovered." He asks to imagine doing long multiplication using Roman numerals. ("It can be done, but it's clunky").

"Arabic language" he says "hasn't changed much in 700 years." We're reminded that algebra, algorithms and alkali are all Arabic words, and that the first - with which Al-Kalilli is especially fascinated and that he makes especially fascinating - underpins modern physics. He talks to current Arab scientists and historians, and refers to his British colleagues for corroboration. He also follows the power and the money.

At its height, the Islamic empire was the largest, and hence the richest, in the world. For scientists "there's nothing like a large chunk of money to focus the mind," and the Caliphs and ruling elites were great dispensers of grants. They were also great bibliophiles. "Bringing books to the Caliph for his library could be very lucrative," there was one who would reward the bearer of a rare book by giving him its weight in gold. (It must have been like an Oprah endorsement.) There was a passionate desire for preservation; the burning of the great library of Alexandria had bequeathed "the ever-present possibility of total loss." Many of these books were classical Greek and Roman texts; so arose the immensely influential Translation Movement which, rendering these texts into Arabic, seems to have anticipated the re-awakening of European humanism by several centuries. The reclaiming of ancient knowledge fed into new Arab science, especially in medicine, which in turn was hugely influential.

"Up until the 19th century" says a medical historian, "Western medicine was built to a large extent on the work of Islamic physicians." They in turn were based on the ancient Greeks, especially on Galen and his "theory of humours" which held that four bodily fluids governed the human mind and body. Anyone who has read an Elizabethan play will have come across this dodgy, if comically fruitful, idea; and will wonder if the two cultures discovered Galen independently of one another, or whether we got it from them. Like much else, it has of course been discredited. The program's verdict on Islamic medicine is that "they took for granted much we know to be nonsense, but their desire to deal with the subject logically and systematically is admirable."

Or, as Al-Khalilli puts it, "the scientific method was discovered by medieval Islam." Perhaps the most startling development of all concerns cartography and its consequences. A Caliph in 813 was "obsessed with measurements - map-making": not surprisingly in view of the amount of territory he had to measure. Also, devout Muslims, spread all over the empire, "needed to know where Mecca was." Working out the precise directions in which they should be looking led geographers to measuring the earth's circumference, and getting a result (40,000 kilometres) very close to the right answer. Al-Khalilli doesn't make much of that word "circumference" but it pulled me up short. You mean they knew, way back then, that the world was round?

Among the scientists' other accomplishments were the anticipation, if not quite the invention, of the periodic table, the use of petroleum in weaponry, and, as one scholar puts it, "the whole idea of the chemical-industrial lab." They also, it seems, invented soap. And a visit to a modern Cairo bazaar produces a pair of carrier pigeons, whose ancestors were "a sort of medieval Telex." One thing that isn't addressed, at least not in the first two programs, is how and why it all stopped: why Islam turned in on itself, why riches stopped promoting knowledge and why - in effect - the Translation Movement went into reverse. What we do get is a stunning inventory, accessibly described and narrated: popular education at its best.

Related Links: