As was the case with most Turkic peoples, genesis of the Crimean Tatars spread through centuries and involved many tribes and peoples inhabiting the Crimean peninsula, including ancient Greeks, Alanes, Khazars, Seljuks, Pechenegs (Pincenates) and Cumans (Kipchaks, Pechenigs).

From time immemorial, there were three dialects of Crimean Tatar language: the Southern, or Coastal dialect belongs to Oguz language family and is the closest to Turkish; the Steppe (Nogay) dialect belongs to Kipchak language family; and the Central dialect traditionally spoken by the Crimean highlanders, which has elements of both the Coastal and the Steppe dialects. This Central dialect is the direct descendant of the ancient Kipchak language; it is from this dialect the modern Crimean Tatar literary language originates.

Boris Kuftin, a Turkologist and a researcher of Crimea, wrote in 1924: “Profound influence of the Southern Turkish Othman language is what differs the speech of the coastal Tatars from that of the other Tatars’ of Crimea… Tatars in Alupka, Yalta, and Gurzuf speak almost pure South Turkish, while Tatars from the mountain villages of Sudak district have distinctive dialect traits, like replacing the soft “k” with “ch”, etc, which can be explained by the influence of Anatolian dialects.”

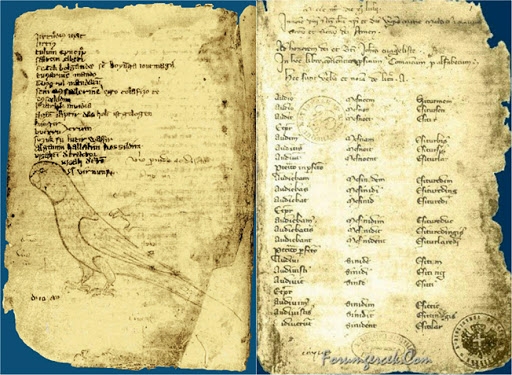

We have a representation of the Crimean Tatar proto language in Codex Cumanicus, a collection written by different authors in different periods. Its oldest part was probably written in XII, while the final part was completed by 1303 somewhere in Crimea (probably, Qafa). Today, copies of Codex Cumanicus can be found in Venice.

Before the Mongol conquest of XIII, Crimea was mostly populated by different Turk peoples, descendants of Khazars, Volga Bulgars, Pechenegs (Pincenates), predominantly Cumans (Kipchaks). Besides, there was a small community of Seljuk Turks who were merchants and vendors. That was the time when Islam was spreading through the peninsula, and by 1260-70ies most Turks, influenced by preachers from Anatolia and Central Asia, converted to Islam. There are few historical documents proving this, but those sources are persuasive.

Commercial activities of the city-states of Venice and Genoa created a demand for knowledge of Turkic languages, especially after the Golden Horde, or Ulus Juchi, emerged as the largest Eurasian state of that period. The Golden Horde’s most used language was Cuman (Kipchak), and most princes of Rus, as well as the elite of Hungary and Transcaucasian states, and much of the affluent Italian merchants. Basically, it was the lingua franca for most of the Eastern Europe and the Black sea region in XIII–XIV.

“A letter from one of the Fratres Minores the Avignon Collegium of Cardinals informs of the reasons why Tatar language is taught at the mission’s school in Qafa. Of course, such teaching would be impossible without textbooks and dictionaries. The school in Qafa may probably have used one of the scrolls of Codex Cumanicus for teaching purposes. Most linguists who studied the Codex positively attribute it to the Crimean Tatar language.”

Some of Europe's most prominent Turkologists like Yaroslav Dashkevych, Alexander Samoylovich and Jean Deny believed Codex Cumanicus to be one of the first written artifacts in Crimean Tatar. Otto Blau in his 1876 work also indicates the direct connection between the Codex Cumanicus and the dialects of the Crimean Tatar language.

Modern Ukrainian researcher Yaroslav Pylypchuk notes that the earliest samples of Kipchak language are represented in “Diwan Lughat al-Turk” or “The Compendium of the Turkic languages” by Mahmoud al-Kashgari. The same is true for the X-XI century Oguz language: al-Kashgari’s work is it’s only documented source. The researcher recited his linguistic findings in Oguz and Kipchak languages, and then compared them to Karakhanid (a literary language closely related to ancient Uighur. — Ed.)

Anna Comnena, a Bysantean historian, mentioned ethnic kinship of Pechenigs and Kipchaks in her work, the Alexiad, and states that “Pechenig and Kipchak people spoke the same language”.

All these records give us a crude understanding of the rich historical heritage the Crimean Tatar language came into during the age of its formation. Having emerged in the early Middle Ages, the Crimean Tatar language reached its full flowering in the Crimean Khanate, where many prominent works (including poetry) and historical chronicles were written.

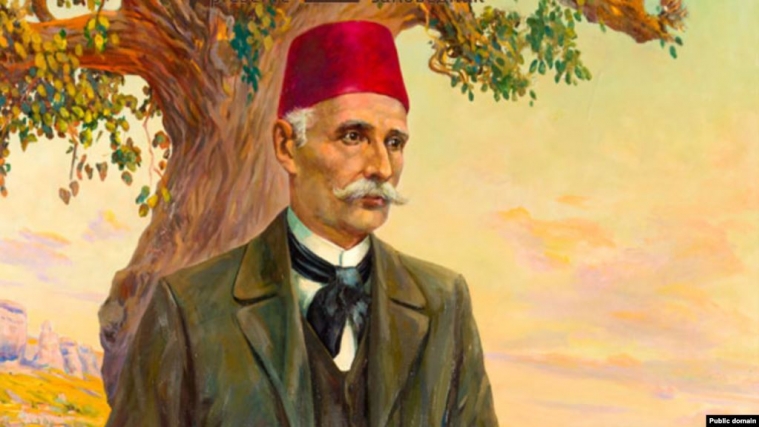

Prominent researcher and educator Ismail Gaspirali, author of numerous works on history and culture of the Crimean Tatars, was both the successor to the tradition and the founder of the new Crimean Tatar literature. A modern Muslim can find several of his works quite interesting, including “The Culture of Islam”, “Lessons for Ramazan”, “The Study of Qur’an Recitation”, “History of Islam”, “Shariah Rules for Fasting”, “The Compendium of Everyday Obligatory Religious Rules for Muslims”, etc.

Ismail Gaspirali had a great impact on the formation of the modern literary Crimean Tatar language. He raised a galaxy of talented intellectuals that carved the Crimean Tatar literature its rightful place in the Global Literature. Gasprali understood the true meaning of native language for Crimean Tatars’ everyday life; he wrote: “No need to mention the importance and the deep meaning of the common literary Crimean Tatar language for publishing and for the readers’ growth. Language is the basic means for developing a nation.”

Thanks to Mr.Gaspirali, Crimea was seen as one of the most important centres of Islamic Renaissance, and the Crimean Tatar was on par with the other Turkic languages.

By Oleksandr Stepanchenko